The New York Times reports that Coca Cola and Pepsi are now locked in an entirely new battle – the race to produce the first plastic bottle made entirely from plant based products. Marketing and sustainability PR benefits aside by being able to claim the first “green” plastic bottle, Coke and Pepsi feel the push for these types of bottle not only helps environmental sustainability in the long run, but also makes more business sense.

The Race to Greener Bottles Could Be Long

Published: December 15, 2011

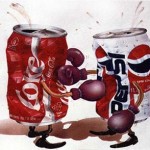

Over their decades of competition, the battle between Coca-Cola and PepsiCo has taken on many colors — brown (cola), orange (juice), blue (sport drinks) and clear (water).

Now, they are fighting over green: The beverage rivals are racing to become the first to produce a plastic soda bottle made entirely from plants.

But despite dueling announcements claiming technological breakthroughs, consumers should not expect to see many all-plant bottles on store shelves any time soon. Neither company is confident enough in the technology to say when, or even if, they will be able to deliver on their environmental ambitions.

Coke delivered the latest volley on Thursday, saying it plans to work with three companies that are developing competing technologies to make plastic from plants, with bottles rolling out to consumers in perhaps a few years.

PepsiCo is aiming to beat that timeline and claim the 100 percent green label first. The company declared in March that it had cracked the code of the all-plant plastic bottle, and on Thursday, it said that it was on schedule to conduct a test next year that involved producing 200,000 bottles made from plant-only plastic. But until Pepsi conducts the test, executives said they would not be able to predict when large-scale production of such bottles might begin. If the test fails to prove that the technologies favored by Pepsi are cost-effective at a commercial scale, more experimentation will be needed, said Denise H. Lefebvre, the company’s vice president for global beverage packaging.

“The test is very important in really determining efficient cost and manufacturing processes,” Ms. Lefebvre said. She said the company was still working out details of the test, including what products to sell in the all-plant bottles and what type of plant materials to use to produce them.

Coke was the first out of the gate in the green bottle race, when in 2009 it began selling Dasani water in the United States in bottles made with up to 30 percent plant-based plastics. (In some cases, recycled plastic may decrease the plant-based amount.) On Thursday the company said that by 2020 all of its plastic bottles would meet the 30 percent plant-based standard. But the company was more cautious about when it could start selling beverages in bottles made entirely from plant materials.

cautious about when it could start selling beverages in bottles made entirely from plant materials.

“We will set the target once we have the commercial technology in place,” said Scott Vitters, the general manager of Coke’s plant bottle packaging platform.

One of Coke’s new partners, Virent, a Wisconsin-based biofuel and chemical company partly owned by Cargill, Shell and Honda, said it hoped to have a large-scale plant to produce plastic for beverage bottles up and running in 2015.

Mr. Vitters would say only that some commercial production of 100 percent plant-based plastic bottles was achievable “in the next few years.” The exception is Coke’s Odwalla juice brand, which already uses all plant-based material to make a type of plastic suitable for juices.

The two other companies working with Coke to develop the all-plant soda bottles are Gevo and Avantium.

Ms. Lefebvre said that Pepsi was following a similar path to the one Coke announced Thursday, teaming up with companies that are developing different ways of solving the plastic puzzle. But she declined to identify the partners.

Soda bottles are made from a type of plastic known as PET, which commonly has two main components. One, called MEG, makes up about 30 percent of a bottle’s weight, and is what Coke has been producing from plant sources, using sugarcane grown in Brazil. The other component, called PTA, makes up 70 percent of a bottle’s weight. Scientists have been able to make PTA from plant materials in the laboratory but pulling off the same trick on an industrial scale has proved more difficult.

Mr. Vitters said that production capacity for MEG, used in the 30 percent plant bottle, was poised to increase drastically. The material is produced in only one facility today, but at least two additional factories are expected to begin production next year.

Allen Hershkowitz, a senior scientist at the National Resources Defense Council, an environmental group, said that the production processes involved in creating plastics from plant sources generated smaller amounts of greenhouse gases, which contribute to climate change, when compared with plastics made from petroleum. But he said the source of the plant materials was important in assessing the environmental impact. Mr. Hershkowitz said that using agricultural waste products, like corn stalks or other materials left over from farming, was better than using crops, such as sugarcane or corn that are grown specifically for plastic production.

Growing crops for plastic “causes a lot of land conversion, it affects the price of food, it uses a lot of fertilizers,” he said.

Pepsi has said it will use agricultural waste products, such as corn husks, pine bark or orange peels, to make its plastic bottles. Mr. Vitters said that Coke might use a variety of materials, including wastes and crops grown for plastic production.

Regardless of how they are produced, Mr. Hershkowitz said that plant-based plastics still create litter and solid waste problems. He said companies like Coke and Pepsi should endorse legislation that would require the food and consumer products industries to finance recycling operations, in order to greatly increase plastic recycling.

Both Coke and Pepsi have broad initiatives to make their operations more environmentally friendly, taking steps to cut back on factors such as water and energy use.

But the companies played down the potential marketing benefits inherent in being the first to the market with an all-plant bottle.

“We don’t feel it’s a race” Ms. Lefebvre said. “We feel like were all working together to do better for the environment and also to make good business sense.”